I’ve always been interested in wild things. For most of my life I have crept and crawled through weed and water to find the herbaceous perennials that flower without Homo sapiens digging and snipping. Once-tame and now-wild also interests me. On a recent trip to Catalina Island off the coast of Southern California I found the bison herd there fascinating. The present-day herd are the progeny of a number of bison brought to the island in 1924 by Zane Gray to be background in a film adaptation of his book The Vanishing American. The film went bankrupt and there was no money to transport the animals back to Yellowstone.

The bison herd on Catalina are managed and now a few of the calves are reintroduced into mainland herds to improve the line. I went with a group of friends on a backcountry trip on the island into the middle of the herd. It is fascinating and a bit emotional to be in the midst of a group of creatures who once defined a geography but now are left to a dingy few. The title of the Zane Gray tome punctured a nerve in my head.

I was invited to mount an exhibition at the Jule Collins Smith Museum on the campus of Auburn University during the fall of 2023. The six-foot by eight-foot painting of the bison on the island was featured one of the galleries.

The bison struck a nerve with me. For years I examined situations where other species were relocated by humans. A trip to the Hawaiian island of Kauai presented a landscape dominated by chickens. Further study showed that the Polynesian colonists brought Red Jungle Fowl to the island more than a thousand years ago. Local lore indicates that these Red Jungle Fowl were joined by domesticated chickens released by hurricane activity during the twentieth century. The result is birds everywhere. I love that they crow at obscene hours dismantling the peaceful slumber of vacationers. The image on this five-foot square surface was compiled at a promontory over the Napali coast on Kauai.

The exhibition at Auburn was part of a series produced by then curator, Aaron Garvey. The series, entitled Radical Naturalism (a term close to my heart), was intended to bring contemporary artist in to mount a visceral response to the museum’s incredible collection of works by nineteenth century naturalist, John James Audubon. While discussing opportunities with the curatorial staff at the Jule, I shifted my focus away from the most widely known Audubon works, the Birds of America.

Late in his life Audubon produced a work with images of mammals, The Quadrupeds of North America. I spent time in the vaults of their collection and selected Audubon prints that would be a part of my exhibition. Above we see on the right the image of a raccoon paired with twelve mixed media pieces of mine. Across the way is a multi-panel composition that memorializes hikes in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina.

Audubon’s fox is paired with my images of southeastern wildflowers

.The ubiquitous Opossum as portrayed by Audubon is shown in conjunction with various images I collected from the wild

.This Sand Hill Altarpiece shows a portrait of Blue, a gorgeous Indigo Snake from Auburn’s Natural History Collection along with the keystone species, Gopher Tortoise and a long-leaf pine cone which symbolized the continuous forest that spread across the pre-colonial South

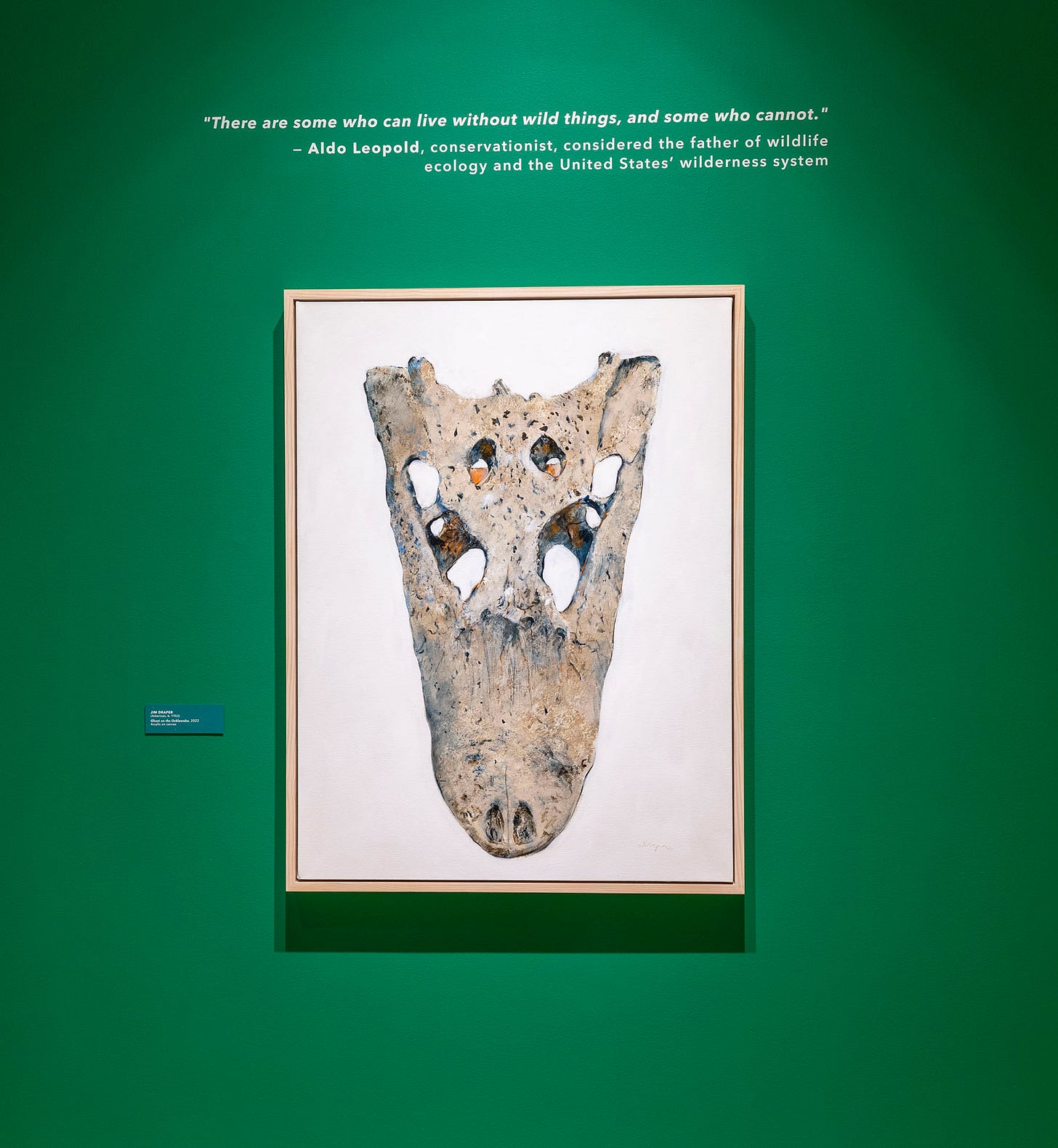

.The image of an American Alligator skull I found while exploring a drawn-down Ocklawaha River in central Florida. This Image, entitled Ghost of the Ocklawaha, lands somewhere between a touchstone and a talisman for me. Moreover it is probably a symbol of what we lose when we lose the wild. Yes, there are points of fear. We are terrified of those creatures lurking in the dark waters and caves of our wild places. But there is one species we should fear the most. One that is Hell-bent on destroying everything good on this planet. It is spotted easily. Glance in a mirror.

👏